Old Wall Street proverb says, “Buy the rumor, sell the fact”. Once upon a time, Wall Street was a real market, the idea back then was for traders to get a jump on the crowd. Smart money anticipates moves, the rest of the market reacts after moves occur. Smart money wins, the dumb money winds up with less, they are the lewzers …

It looks like the smart crude oil money is heading for the exits:

Energy Commodity Futures

| Commodity | Units | Price | Change | % Change | Contract |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude Oil (WTI) | USD/bbl. | 91.97 | -1.64 | -1.75% | Jul 13 |

| Crude Oil (Brent) | USD/bbl. | 100.39 | -1.80 | -1.76% | Jul 13 |

| RBOB Gasoline | USd/gal. | 277.89 | -3.36 | -1.19% | Jul 13 |

| NYMEX Natural Gas | USD/MMBtu | 3.98 | -0.04 | -0.97% | Jul 13 |

Keep in mind, futures’ prices are benchmarks that do not reflect prices in cash- or over the counter markets.

World crude prices @ $100 per barrel or below are dangerous because so much of the revolutionary new forms of ‘crude oil’ are costly to bring to market.

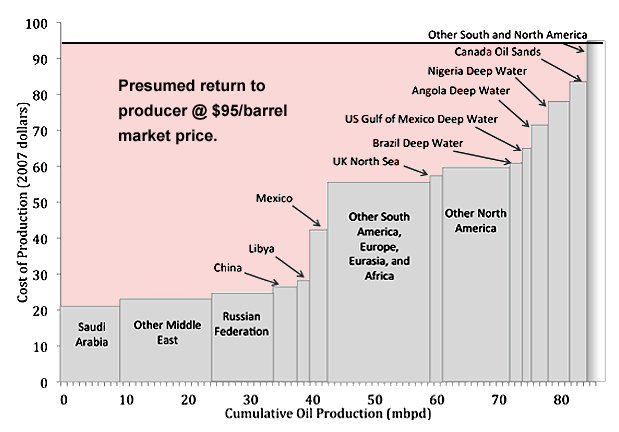

Figure 1: Marginal cost of a barrel of crude oil from David Murphy (The Oil Drum) in late 2010. Marginal production costs relentlessly increase, they are much higher now. US conventional crude returns a profit to the producers at current WTI price but profits shrink with price declines. Enough declines and there are no profits — and less crude.

The marginal price is one where the customer decides that extra barrel is not worth it. Customer choice being what it is, the price of the sainted marginal barrel becomes the price for all the other barrels. What is magic about the entire process is that any garden-variety barrel of oil in any part of the world can become the marginal barrel. If marginal barrel is low-cost, the high-cost varieties are left out in the cold.

This is okay if there are a bazillion barrels of low cost crude ready to sell, not okay when low cost supplies are being continually depleted and are largely gone. When the $100 dollar crude is out of reach, there is nothing cheaper to replace it.

When the little man in the TV talks about frakking and ‘revolutions’ he’s lying. What he leaves out is that the customers are flat broke and cannot afford to buy fuel, nor can they afford to borrow. ‘Broke’ is why oil prices are declining, not an excess of supply.

As with most other aspects of our ‘Economy of Stupid’ we have painted ourselves into a corner of our own making. We need continual monetary easing from central banks to bail out finance, yet the costs of easing to everyone besides finance are unbearable. We need finance because the precious industries we have invested so much in the way of resources and prestige over the past decades cannot pay their own way; without finance, there is no industry. We need government borrowing to service finance’s debts even as the borrowing itself increases the dead-weight burden of those same debts. We need high crude prices to meet the costs providing new energy sources but the required prices are bankrupting us.

We’re stuck … everything we try to keep the status quo intact makes everything worse. We need to back out of the box(es) we’ve wedged ourselves into but we refuse to even consider it. We keep believing that tomorrow Santa Claus will arrive with the elf-magic needed to rescue us from our own follies. We cram ourselves more tightly into the corners, inch further into the rat holes, creep closer to the abysses … we are at the point where we have run out of room …

Rumor has it, the smart money has shorted Santa Claus …

Note the inflated returns to many of the low-cost producers. The high marginal cost is a perverse incentive for the low-cost producers to exhaust their petroleum capital as rapidly as possible, to trade it for empty promises of future ‘prosperity’. The greater returns allow producers to load up on luxury autos, strip malls, high-rises, fashionable-but-money-losing ‘development’ projects, military hardware and other forms of resource waste. This in turn adds more incentives for the producers to exhaust their capital even faster and more completely.

The conventional economic assumption has been that crude oil customers products are unaffected by price increases; that the economy will run in the background as usual regardless of input cost. Taken a step further, this ‘price signal’ is offered as a component of the economy’s ordinary function; the higher price is incentive to increase supply. This assumption is false for two reasons:

The first is that using more costly fuel does not produce any more goods or services than using the cheap stuff. Goods and services matter; our economies are much more than pumping oil. When crude prices increase, there is demand for additional credit. Because there is no increase in real goods to swap for fuel, customers can only meet the higher price by borrowing more. The outcome is rationing fuel by borrowing until credit itself becomes too costly, after which point there are physical shortages of fuel.

The second is that cost- or money-return does not effect geology. High-priced technology cannot magically produce oil or any other resource where it does not exist. The roughly 10x increase in crude market price from $11 per barrel in 1998 to $104 now has not resulted in 10x increase in crude production. The rate of crude extraction has remained at more or less the same level since 2005.

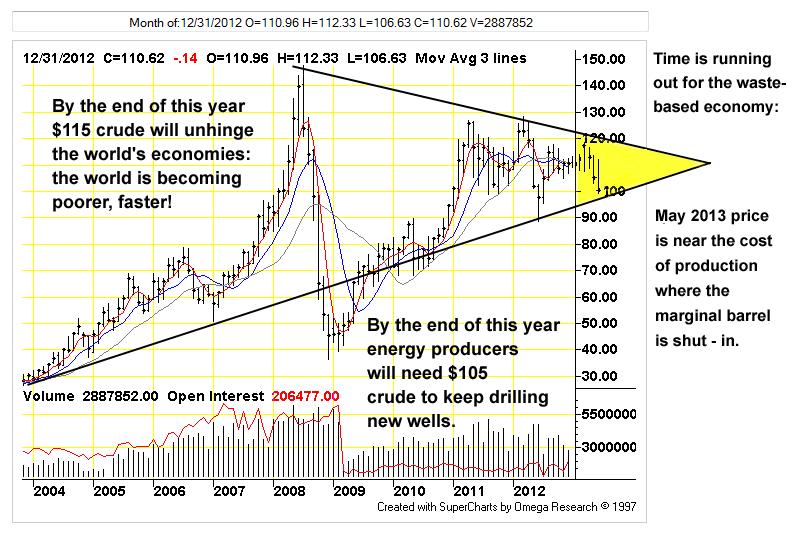

Figure 2: Oil company costs from Goldman-Sachs, (click on for big): today’s crude producers are tomorrow’s gold miners, trapped by high costs. When the marginal drillers fail, the failure effects all the other actors within the space … who require credit to meet their own costs. Major international companies and national producers have greater borrowing capacity than the marginal producers but such capacity is not infinite. Worst case scenario is that drillers become wholly-subsidized wards of the various sovereigns within command economies but that lasts only as long as the sovereigns themselves are credible borrowers. When the sovereign is borrowing from itself it cannot subsidize anything.

With depletion, the fuel price continues to increase relative to all other prices: this is the ‘real’ fuel price. Fuel is embedded in all goods and services; energy costs across the product spectrum are cumulative. When nominal fuel prices increase customers cannot keep up, when the nominal fuel price declines, the ability of customers to meet that price declines faster. The process feeds on itself as energy deflation, similar to Irving Fisher’s debt deflation. There is no possible way to win.

Figure 3: The crude oil dilemma in one chart: Continuously increasing nominal prices are needed by drillers to bring new crude to the marketplace. (Click on for big): Chris Nelder:

The advent of tight oil in the U.S. has been hailed as the beginning of our incipient energy independence, although I have found no basis for such optimism in the data. In fact, this is the third or fourth time we have been treated to such cornucopian stories. A few years ago it was biofuels that would save us from peak oil, and before that it was natural gas liquids, deepwater oil, heavy oil, tar sands and coal-to-liquids. One need look back no farther than 2005 to find plenty of pollyannish projections in reports from the EIA and IEA, and in op-eds in the Wall Street Journal. None of those projections panned out.The argument was that high oil prices would make these previously-uneconomic resources viable, and to a limited extent that has been true. What we didn’t know then, however, was the pain tolerance limit of consumers. In 2008 we found that limit as we approached $120 a barrel for oil and $4 a gallon for gasoline. Prices are once again beginning to kill demand in the U.S., but under a slightly lower ceiling, because the economy isn’t nearly as strong as it was in the first half of 2008. Now the ceiling is closer to $100 a barrel.

The pain tolerance was assumed, anyone with basic observational skills could see the massive investment in consumption infrastructure would never provide any return at all with crude priced above $20 per barrel. At the higher current price, the burdens on credit providers — and borrowers — are crushing.

From $147, crude at the current price is expensive enough to destroy economies. Soon enough, $90 crude will be doing the dirty deeds: China’s economy slinks off to die in agony as per to its own PMI report. Overseas customers enduring depressions cannot afford to buy Chinese exports which in turn effects Chinese consumption, (Radio Free Asia):

After years of great gains, the slowdown of the country’s economic expansion has taken a toll on oil demand growth. In March, China’s apparent oil demand rose only 1.9 percent from a year earlier and fell 4.2 percent from February to 9.7 million barrels per day, Platts energy news service said. Oil imports in the first quarter dropped 2.3 percent to 5.6 million barrels per day, according to General Administration of Customs data.The oil figures are the latest in a string of energy results that reflect economic cooling with official growth for the first quarter of 7.7 percent. Herberg said weakness in demand for oil, coal and power is a sign that heavy industry has been hit by the economic slowdown.

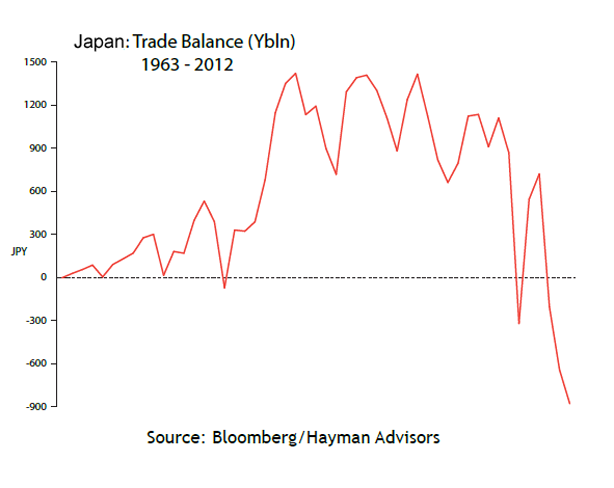

Like the rest, the China establishment lies about its economy, the fact of the lie speaks for itself. Meanwhile, Japan is blowing up …

Figure 4: From Kyle Bass & above by way of Mauldin-Grant Williams: Japan’s trade surplus is gone; the swan song of Japanese exporters and the end of overseas’ subsidies for Japan’s own wasteful consumption. Mercantilism is nothing more than beggaring one’s neighbors by offering junk in exchange for value. Japan’s trading partners are broke, they cannot support themselves, they certainly cannot subsidize Japan any longer. The partners are broke because Japan never offered products that preserved the trading partners’ capital, only products that destroyed it.

Japan prolongs the agony by attempting to borrow from itself hoping nobody notices.

Robert Rapier, (The Oil Drum):

A question I frequently encounter is, “How high could gasoline prices ultimately rise in the U.S.?” Because the oil markets are global, the answer to that question is, “It depends on how much value people in developing countries place on increasing their oil consumption to two or three barrels of oil per year.” Or, an alternative way to think about it is, “If you were only allocated 3 barrels of oil per person per year, how much would you be willing to pay for those barrels?” The 20th barrel the average person in the U.S. consumes each year might allow us to drive that 12,000th mile. But the first barrel that someone in a developing country consumes might allow them to drive that very first mile and have heat in their home for the first time. They will be willing to pay a lot more for those initial barrels than we are for our excess barrels, and this explains why their consumption has increased even as oil prices have risen.

And if future oil prices are dictated by how much developing countries are willing to pay for their second or third barrel of oil per capita, this number may ultimately be much higher than $100 per barrel. This is a major reason that I don’t ever foresee a sustained return to cheap oil. There are many who have placed most of the blame for increased oil prices on speculation, but the thirst for oil in developing reasons means that there are fundamental issues of supply and demand at work as well.

A variation on this theme is that the people in developing countries buy more efficient products that use less fuel which allows them to bid more for each barrel of oil.

It is most likely that these countries are subsidized like the Japanese by the US current account- and trade deficits. As US customers go broke and money becomes tighter, fewer dollars will flow overseas, there will be less collateral for loans offered in local currencies, fewer dollars will be offered in exchange for crude oil. The result will be more of the same: less consumption, lower crude prices, more supply taken off-line and recessions.